Ruta chalepensis L.

"There's fennel for you, and columbines:

there's rue for you; and here's some for me:

we may call it herb-grace o' Sundays:

O you must wear your rue with a difference..."

(In:William Shakespeare's Hamlet (IV.5))

When I mention the family Rutaceae, it may recall the scent of Citrus groves to those who have visited Chania, for oranges and lemons are the most important fruits of the Rutaceae (and of Chania). The name of renowned German taxonomist Engler is most closely linked with the family Rutaceae, for he wrote several important papers about this family, but also extensively discussed every taxonomical and anatomical detail of every known member in hundreds of pages, with many excellent illustrations, in both editions of his great work, “Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien”.

The family consists of about 150 genera with about 1500 species. The type genus is Ruta, with about 60 species distributed from the Atlantic Islands through the Mediterranean region all the way to Asia.

The type species of the Rutaceae is Ruta graveolens L., an odorous herb of southern Europe: it is not in the wild in Crete but I expect that that won’t take long, because you can find it in every flower- or garden-shop and it’s just a matter of time until it escapes; therefore before the end of this page I shall devote a little space to R.graveolens. Another famous member that you will probably meet in the municipally of Chania is Citrus, and I shall ask your attention for some interesting details of Citrus as well at the end of this page.

I knew Ruta chalepensis from the botanical gardens of the Wageningen University, and from another place that I try to avoid as long as I can: the practice of my dentist, where it grows in front. When I found it again in the gorge of Messavlia, I took the time for a closer look.

The family consists of about 150 genera with about 1500 species. The type genus is Ruta, with about 60 species distributed from the Atlantic Islands through the Mediterranean region all the way to Asia.

The type species of the Rutaceae is Ruta graveolens L., an odorous herb of southern Europe: it is not in the wild in Crete but I expect that that won’t take long, because you can find it in every flower- or garden-shop and it’s just a matter of time until it escapes; therefore before the end of this page I shall devote a little space to R.graveolens. Another famous member that you will probably meet in the municipally of Chania is Citrus, and I shall ask your attention for some interesting details of Citrus as well at the end of this page.

I knew Ruta chalepensis from the botanical gardens of the Wageningen University, and from another place that I try to avoid as long as I can: the practice of my dentist, where it grows in front. When I found it again in the gorge of Messavlia, I took the time for a closer look.

|

One of the things that fascinates me most about this plant, are the fringed petals. In the tropics fringed flowers are not so rare (for example the family Cassipourea) but in Crete or the Netherlands I only know two or three other plants with dentate or ciliate petals. Ruta chalepensis is not rare in Crete. It was (and sometimes still is) used in the kitchen and as a medicine and you’ll have a good change to find it around ruins and long-abandoned houses, and for the smell and appearance it is often used in gardens.

|

Now, please come a little bit closer and take a look at Ruta chalepensis L.

The common names are Fringed rue, Aleppo rue, Egyptian rue.

It is native to the Mediterranean and the Balkans.

Fringed Rue is a small yellowish-grey-green shrub-like plant of 20 – 80 cm height, a perennial herb that is more or less woody below.

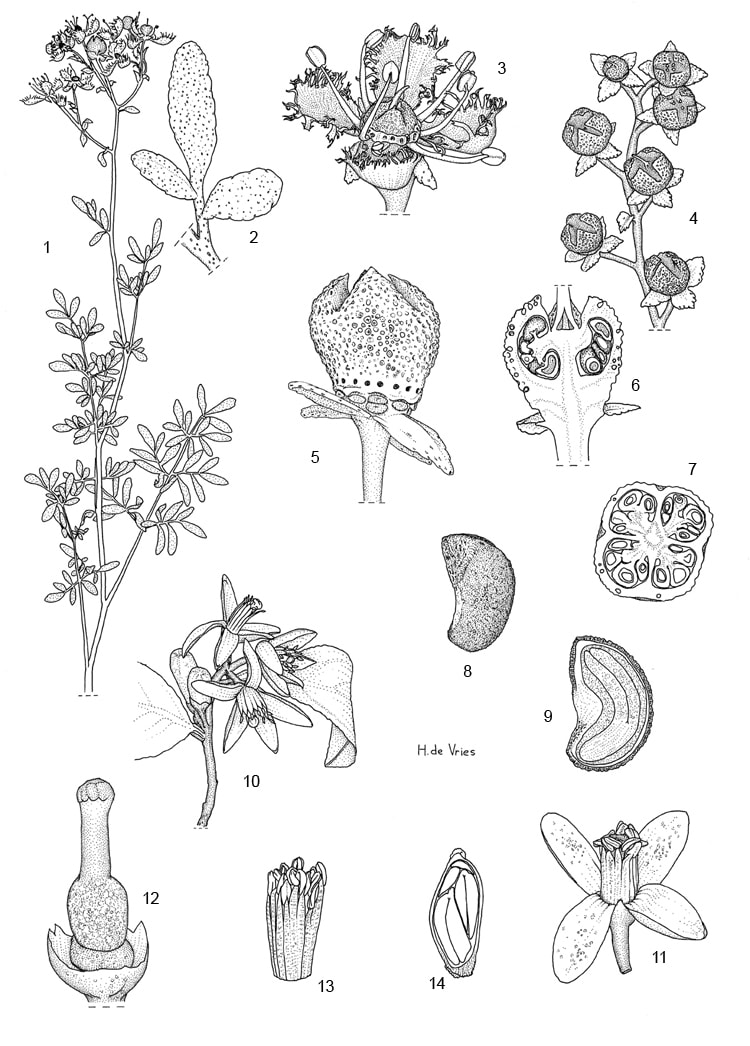

The leaves are generally 10–20 cm, prominently dotted with oil-glands (see detail “2”) and strong-smelling, twice or three times pinnately divided (bipinnate or tripinnate, giving them a feathery appearance), with oblong-elliptic to linear segments with entire border (in R.graveolens the segments are much rounder). The lower leaves have (more or less) long stalks and the lower bracts are much wider than the branches which they subtend; the plant is glabrous throughout.

The inflorescence: they are, usually, plants with loose cymose clusters of yellow flowers.

The common names are Fringed rue, Aleppo rue, Egyptian rue.

It is native to the Mediterranean and the Balkans.

Fringed Rue is a small yellowish-grey-green shrub-like plant of 20 – 80 cm height, a perennial herb that is more or less woody below.

The leaves are generally 10–20 cm, prominently dotted with oil-glands (see detail “2”) and strong-smelling, twice or three times pinnately divided (bipinnate or tripinnate, giving them a feathery appearance), with oblong-elliptic to linear segments with entire border (in R.graveolens the segments are much rounder). The lower leaves have (more or less) long stalks and the lower bracts are much wider than the branches which they subtend; the plant is glabrous throughout.

The inflorescence: they are, usually, plants with loose cymose clusters of yellow flowers.

The pedicels are as long as or longer than the capsule; the branches and pedicels are glabrous with rarely a very few minute glands above; the bracts are wider than the subtended branch, the lower several times so.

|

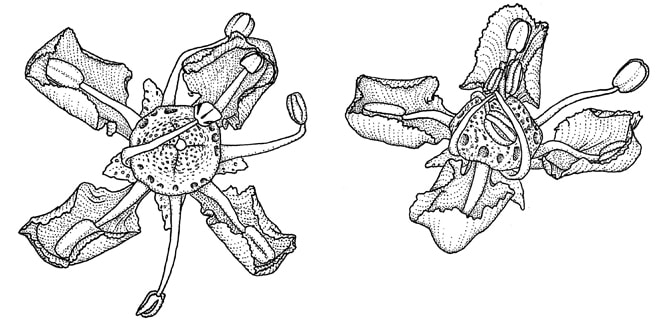

The scented flowers are about 2 cm across, normally with 4 sepals and petals, or frequently with 5 only on the central (“first”) flower of each inflorescence.(see http://delta-intkey.com/angio/images/rutac317.gif).The petals are oblong and conspicuously fringed with long cilia not as long as the width of the petals, 6–8 mm, yellow, with their margins inrolled. (in R.graveolens the petal margin is entire, only wavy). There are as many stamens as petals plus sepals : 8 (or 10) in 2 series.

|

These stamens mature in two waves: first “enroll” and open the stamens that stand in front of the sepals, while the epipetalous stamens lay in the curve of the petals; then these stamens rise and open.

The sepals are also glabrous, deltate-ovate

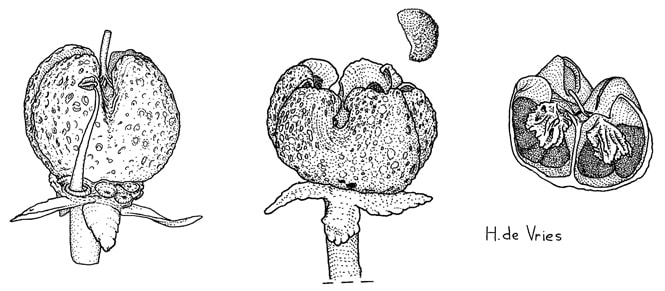

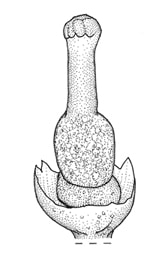

The ovary is superior. The floral receptacle (the “bottom”of the flower where anthers, petals and so on are attached) has been developed into a gynophore. As in all Rutaceae, there is a hypogynous disk. This disk can be seen (in detail 5) as the ring under the ovary with the large glands (the large glandular pits).

It flowers from April until June.

The capsule is 4-lobed (or in the central flower of each inflorescence: 5-lobed). The styles come from every lobe but soon fuse into one style (see details 5 and 6).

The fruit has long-pointed erect lobes (see “5”, and that is the third difference with R.graveolens who has more rounded lobes). The seeds are many and are angled.

You can find the Fringed rue in rocky places in the Mediterranean region, in the gorges of Crete, in the montane and sub-montane zones in rocky places, in the edges of woods, dry banks and thickets, usually on limestone.

Because it is quite hardy, it has been introduced in most parts of Europe and in California,USA.

There are some different opinions about its usefulness. It is still in cult for ornamental, flavoring and medicine.

It was used extensively in the middle eastern cuisine in the old times, as well as in many ancient Roman recipes, but because it is very bitter, it has fallen out of grace as not being suitable for our modern taste. However, it is still used in certain parts of the world, particularly in northern Africa, several Arabian countries, India and Mexico. It is reported that the leaves are used as a condiment and that a decoction of the plant has been used in the treatment of coughs and stomach aches.

An essential oil obtained from the leaves is used in perfumery and as a food flavouring.

However, a warning is in its place here. There are several reports that some toxic oils may promote localized sunburn or produce dermatitis. There are many reports on the internet that picking leaves or flowers can produce contactdermatitis.

In a report on pharmaceutical compositions and methods at www.freepatentsonline.com/6811795.html we read that the aerial parts of Ruta chalepensis are used to produce medicines. In Saudi Arabia, for example, the aerial parts of the plant are used as a laxative and anti-inflammatory, and to treat colic, headache and rheumatism. In India, the plant is prescribed for dropsy, neuralgia, rheumatism, and menstrual and other bleeding disorders. In Africa, an aqueous decoction of the leaves serves as a treatment for fevers (Shah et al., J Ethnopharmacol (1991) 34: 167-72); (Al-Said et al., J Ethnopharmacol (1990) 28: 305-312).

In Crete, infusions of the leaves of the plant are know for use as stomach tonics. Ruta chalepensis is also used, in combination with other herbs, in preparations for tooth and ear aches.

Some North American sources have treated rue as a deadly poison, but this seems exaggerated. Ruta chalepensis is now included on the FDA's GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) list (www.ars-grin.gov/duke/syllabus/gras.htm, not under Ruta but under rue and R., but with a remarknot to exceed 10 ppm.!).

However, larger intakes of the plant and especially the roots, are in most above-mentioned countries known to work as aborticides, and several reports make mention of deaths as a result of bleedings after abortus or poisoning by rue. Fresh rue contains volatile oils that can damage the kidneys or liver. Even though rue is a mainstay of midwives in many developing countries, its risks generally outweigh any benefits it might have for contraception or abortion. Deaths have been reported due to uterine hemorrhaging caused by repeated doses of rue. Taking it orally is strongly discouraged.

Rue is NOT included in C.Fournaraki’s list of Wild Greens Consumed Domestically In Crete.

So, little amounts used as a spice in the kitchen or used as a medicine against stomach-problems seem safe, larger amounts should be avoided.

I’ll come back at this point in my remarks on Ruta graveolens.

Synonyms for R.chalepensis are:

Ruta bracteosa (DC.), R. chalepensis var. bracteosa and Ruta angustifolia (Pers.). Also, the name is regularly mistakenly written as chalapensis, chalepense and so on.

In Platanias, Chania, I found the closely related Ruta graveolens in a flower-and-garden-shop, and you’ll probably find it in many more shops. Because the plant is self-compatible, that means there is a great change that it will one day escape from someone’s garden into the neighbouring nature. So, let’s take a brief look at

The sepals are also glabrous, deltate-ovate

The ovary is superior. The floral receptacle (the “bottom”of the flower where anthers, petals and so on are attached) has been developed into a gynophore. As in all Rutaceae, there is a hypogynous disk. This disk can be seen (in detail 5) as the ring under the ovary with the large glands (the large glandular pits).

It flowers from April until June.

The capsule is 4-lobed (or in the central flower of each inflorescence: 5-lobed). The styles come from every lobe but soon fuse into one style (see details 5 and 6).

The fruit has long-pointed erect lobes (see “5”, and that is the third difference with R.graveolens who has more rounded lobes). The seeds are many and are angled.

You can find the Fringed rue in rocky places in the Mediterranean region, in the gorges of Crete, in the montane and sub-montane zones in rocky places, in the edges of woods, dry banks and thickets, usually on limestone.

Because it is quite hardy, it has been introduced in most parts of Europe and in California,USA.

There are some different opinions about its usefulness. It is still in cult for ornamental, flavoring and medicine.

It was used extensively in the middle eastern cuisine in the old times, as well as in many ancient Roman recipes, but because it is very bitter, it has fallen out of grace as not being suitable for our modern taste. However, it is still used in certain parts of the world, particularly in northern Africa, several Arabian countries, India and Mexico. It is reported that the leaves are used as a condiment and that a decoction of the plant has been used in the treatment of coughs and stomach aches.

An essential oil obtained from the leaves is used in perfumery and as a food flavouring.

However, a warning is in its place here. There are several reports that some toxic oils may promote localized sunburn or produce dermatitis. There are many reports on the internet that picking leaves or flowers can produce contactdermatitis.

In a report on pharmaceutical compositions and methods at www.freepatentsonline.com/6811795.html we read that the aerial parts of Ruta chalepensis are used to produce medicines. In Saudi Arabia, for example, the aerial parts of the plant are used as a laxative and anti-inflammatory, and to treat colic, headache and rheumatism. In India, the plant is prescribed for dropsy, neuralgia, rheumatism, and menstrual and other bleeding disorders. In Africa, an aqueous decoction of the leaves serves as a treatment for fevers (Shah et al., J Ethnopharmacol (1991) 34: 167-72); (Al-Said et al., J Ethnopharmacol (1990) 28: 305-312).

In Crete, infusions of the leaves of the plant are know for use as stomach tonics. Ruta chalepensis is also used, in combination with other herbs, in preparations for tooth and ear aches.

Some North American sources have treated rue as a deadly poison, but this seems exaggerated. Ruta chalepensis is now included on the FDA's GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) list (www.ars-grin.gov/duke/syllabus/gras.htm, not under Ruta but under rue and R., but with a remarknot to exceed 10 ppm.!).

However, larger intakes of the plant and especially the roots, are in most above-mentioned countries known to work as aborticides, and several reports make mention of deaths as a result of bleedings after abortus or poisoning by rue. Fresh rue contains volatile oils that can damage the kidneys or liver. Even though rue is a mainstay of midwives in many developing countries, its risks generally outweigh any benefits it might have for contraception or abortion. Deaths have been reported due to uterine hemorrhaging caused by repeated doses of rue. Taking it orally is strongly discouraged.

Rue is NOT included in C.Fournaraki’s list of Wild Greens Consumed Domestically In Crete.

So, little amounts used as a spice in the kitchen or used as a medicine against stomach-problems seem safe, larger amounts should be avoided.

I’ll come back at this point in my remarks on Ruta graveolens.

Synonyms for R.chalepensis are:

Ruta bracteosa (DC.), R. chalepensis var. bracteosa and Ruta angustifolia (Pers.). Also, the name is regularly mistakenly written as chalapensis, chalepense and so on.

In Platanias, Chania, I found the closely related Ruta graveolens in a flower-and-garden-shop, and you’ll probably find it in many more shops. Because the plant is self-compatible, that means there is a great change that it will one day escape from someone’s garden into the neighbouring nature. So, let’s take a brief look at

Ruta graveolens L.

The Common Rue (Ruta graveolens), also known as Herb-of-grace

Rue is considered the national plant of Lithuania. It is an attribute of young girls, associated with virginity and maidenhood. Therefore it is frequently used in Lithuanian folks songs. A bride traditionally wears a little crown made of rue, the symbol of maidenhood. During the wedding the crown is burned.

In traditional English folk songs thyme is frequently used to symbolize virginity and rue is used to symbolize the regret that is supposed to follow the loss of virginity.

Rue is sometimes grown as an ornamental plant in gardens for its tolerance of hot and dry soil conditions – I found it in a garden in Kalamaki, Chania.

Ruta graveolens is a little smaller than R.chalepensis. The 2 – 3 times pinnately divided leaves of common rue are more blue-green. It is also a shrub-like perennial herb, up to 45 cm with oblong or obovate, glandular-punctate and strong-smelling leaves.

The inflorescence of yellow flowers are rather loose; the pedicels are approximately as long as the capsule; the bracts are lanceolate and leaf-like.

The 4 (again: in the central flower 5) undulate petals have, at the most, finely toothed but in most plants entire and wavy margins, without the long cilia of R.chalepensis.

Rue is considered the national plant of Lithuania. It is an attribute of young girls, associated with virginity and maidenhood. Therefore it is frequently used in Lithuanian folks songs. A bride traditionally wears a little crown made of rue, the symbol of maidenhood. During the wedding the crown is burned.

In traditional English folk songs thyme is frequently used to symbolize virginity and rue is used to symbolize the regret that is supposed to follow the loss of virginity.

Rue is sometimes grown as an ornamental plant in gardens for its tolerance of hot and dry soil conditions – I found it in a garden in Kalamaki, Chania.

Ruta graveolens is a little smaller than R.chalepensis. The 2 – 3 times pinnately divided leaves of common rue are more blue-green. It is also a shrub-like perennial herb, up to 45 cm with oblong or obovate, glandular-punctate and strong-smelling leaves.

The inflorescence of yellow flowers are rather loose; the pedicels are approximately as long as the capsule; the bracts are lanceolate and leaf-like.

The 4 (again: in the central flower 5) undulate petals have, at the most, finely toothed but in most plants entire and wavy margins, without the long cilia of R.chalepensis.

The disk is thick and urceolate, with 8-10 glands or 8-10 glandular pits.

The fruit has 4(5) blunt spreading lobes. indehiscent or dehiscent at the apex

The fruit has 4(5) blunt spreading lobes. indehiscent or dehiscent at the apex

It comes originally from the Balkan peninsula and the Krym, but is introduced, many centuries ago, in parts of northern Europe. Now it is widely naturalized from gardens in S. & S.C.Europe, and also introduced in the Greek mainland – but not yet in Crete.

Rue as a spice:

Rue does have a culinary use if used sparingly but it is incredibly bitter. Fresh leaves are used; if not available, dried leaves, but these are a poor substitute and even more bitter.

Rue was a very common spice in ancient Rome, but because of its bitter taste, its name became an equivalent of “bitterness” in poetry and this gave way to an almost universal rejection in our time. Today, rue is sometimes used as a traditional flavouring in Greece and other Mediterranean countries. In Istria, there is a grappa/rakija recipe that uses a branch of rue.

Apart from some occasional use in Italy, rue is especially popular in Ethiopia, where not only rue leaves are used, but also dried fruits (the rue berries) with their more intensive, slightly hot flavour that is well preserved on drying.

The bitter taste can be reduced by using acids. A rue leaf therefore can be used to flavour pickled vegetables, a little in a salad or in a home-made herbal vinegar, in a spicy tomato sauce together with olives, capers, marjoram and basil. A safe way to use rue leaves, is to add some to the sauce for one minute to solve the flavours of the essential oil and than remove and discard the leaves so that you’ll have the flavour but not the bitterness. But take care not to overdose, because the taste is really bitter.

The bitter rue is also popular for flavouring liquors. A well known Italian liquor is grappa con ruta, a brandy flavoured with a small branch of Fringed Rue in each bottle.

More information about its use can be found in the Spice Pages: www.uni-graz.at/~katzer/engl/Ruta_gra.html

Pliny the Elder describes it as a strong medicine for inducing abortion and it is still used for that purpose in some parts of the world (New Mexico).

Because of its smell, rue can be used in the garden as a deterrent to cats.

It is insensible for moulds and aphids and is used regularly in the biological battle against plant-diseases by alternating sensitive plants with rue.

About the name:

1) the origine of the (originally Greek) name Ruta is unknown, although most Western European languages use similar names: English and French rue, Dutch ruit, German Raute;

2) graveolens comes from Latin ‘gravis’ meaning heavy, strong and ‘olens’ (from ‘olere’) meaning smell, consequently: strong smelling

Common names: Rue, Common rue, Garden rue, Herb of Grace

"Absinthe and Rue

twisted wings of paranoia

twilight runs through eyes of ignorance..."

(from the progressive metal band Symphony X and their song "Absinthe and Rue")

There is another Rutaceae that we’ll regularly meet in Chania, and that is:

Rue as a spice:

Rue does have a culinary use if used sparingly but it is incredibly bitter. Fresh leaves are used; if not available, dried leaves, but these are a poor substitute and even more bitter.

Rue was a very common spice in ancient Rome, but because of its bitter taste, its name became an equivalent of “bitterness” in poetry and this gave way to an almost universal rejection in our time. Today, rue is sometimes used as a traditional flavouring in Greece and other Mediterranean countries. In Istria, there is a grappa/rakija recipe that uses a branch of rue.

Apart from some occasional use in Italy, rue is especially popular in Ethiopia, where not only rue leaves are used, but also dried fruits (the rue berries) with their more intensive, slightly hot flavour that is well preserved on drying.

The bitter taste can be reduced by using acids. A rue leaf therefore can be used to flavour pickled vegetables, a little in a salad or in a home-made herbal vinegar, in a spicy tomato sauce together with olives, capers, marjoram and basil. A safe way to use rue leaves, is to add some to the sauce for one minute to solve the flavours of the essential oil and than remove and discard the leaves so that you’ll have the flavour but not the bitterness. But take care not to overdose, because the taste is really bitter.

The bitter rue is also popular for flavouring liquors. A well known Italian liquor is grappa con ruta, a brandy flavoured with a small branch of Fringed Rue in each bottle.

More information about its use can be found in the Spice Pages: www.uni-graz.at/~katzer/engl/Ruta_gra.html

Pliny the Elder describes it as a strong medicine for inducing abortion and it is still used for that purpose in some parts of the world (New Mexico).

Because of its smell, rue can be used in the garden as a deterrent to cats.

It is insensible for moulds and aphids and is used regularly in the biological battle against plant-diseases by alternating sensitive plants with rue.

About the name:

1) the origine of the (originally Greek) name Ruta is unknown, although most Western European languages use similar names: English and French rue, Dutch ruit, German Raute;

2) graveolens comes from Latin ‘gravis’ meaning heavy, strong and ‘olens’ (from ‘olere’) meaning smell, consequently: strong smelling

Common names: Rue, Common rue, Garden rue, Herb of Grace

"Absinthe and Rue

twisted wings of paranoia

twilight runs through eyes of ignorance..."

(from the progressive metal band Symphony X and their song "Absinthe and Rue")

There is another Rutaceae that we’ll regularly meet in Chania, and that is:

Citrus

Oranges and lemons are probably the world’s most popular and recognizable fruits. These fruits are hesperidiums, because of their fleshiness and separable rind. They contain about forty-five percent juice, about thirty percent rind and about twenty five percent pulp and seeds. They contain about ninety percent water, about five percent sugars and one or two percent acids, protein like vitamines, oils and minerals.

As Tutin in Flora Europaea says: it is a genus of considerable taxonomic difficulty. Some well known members in the Citrus family are: the citron (C.medica L.), the sour orange (C.aurantium L.), the pummelo (C.maxima Merril, formerly C.grandis Osbeck), the lemon (C.limon Burm.fil.), the tangerine (C.reticulata (Blanco), the lime (C.aurantifolia Christm.), and the grapefruit (C.maxima var. racemosa, formerly called C.paradisi Macf.), the sweet orange (C.sinensis), the mandarin (C.deliciosa).

However, some of the above mentioned species are of hybrid origin and there is much confusion about the genuine species within the genus Citrus. Some taxonomists recognize up to 170 species, others argue that all belong to only one large species because they are freely graft and cross-compatible for the most part.

In the Flora Europaea Tutin describes 8 european species:

1.C.medica L. (citron).

2.C.limon (L) Burm.fil. (lemon).

3.C.limetta Risso. (sweet lime). According to Tanaka (1954), a mutant of 2

4.C.deliciosa Ten. (Tangerine).

5.C.paradisi Macfadyen (grapefruit).

6.C.grandis (L) Osbeck (shaddock, pomelo).

7.C.auranthium L. (seville orange).

8.C.sinensis (L) Osbeck. (Orange).

Polunin mentions only three species, cultivated for their fruits and aromatic oils in Greece and the Balkans:

1.C.aurantium L. (seville orange)

2.C.sinensis (L) Osbeck (sweet orange)

3.C.limon (L) Burm.fil. (lemon)

Based on morphological and biochemical characteristics it has been proposed that the cultivated Citrus species comprises four original species of Citrus and that all the others are hybrids. These four basic species are: C.halimii Stone, C.medica L.(the citron) is perhaps the progenitor species for all acid citrus like lemons and limes, C.reticulata Blanco is perhaps the ancestor of all oranges and tangerines, and C.maxima (Burm.)Merril (syn. C.grandis) is the pummelo and shaddock and is probably the ancestor of the grapefruit.

However, recently (2007) using a novel DNA fingerprinting technique called AFLP, Xiao-Ming Pang et al suggest three ancestral species: C.medica (as ancestor of the sweet oranges and mandarins), C.grandis (as the ancestor of the grapefruits and pomelos) and C.reticulata (as ancestor of the lemons, limes and citrons).

All the other “species” are hybrids resulting from different combinations between these three ancestral species: ancestors crossed with ancestors, ancestors crossed with hybrids and hybrids crossed with hybrids, and crossings with Fortunella, Poncirus and other closely related genera. It has been suggested that both the sour orange and the sweet orange are hybrids between mandarin and pomelo; the clementine seems to be a hybrid between the mandarin and the sweet orange (which was already a hybrid between ......). Lemons are probably a cross between a citron and a sour orange (itself probably a hybrid of pummelo and mandarin).

The multitude of natural hybrids and cultivated varieties, including many spontaneous mutants, obscure the search for the center(s) of origin of citrus fruits. The origin of the citrus fruit trees is in the region of China and Southeast Asia and India. Far before the Common Era lemons, limes and oranges were cultivated in the Indus Valley and the citron was well known in the Mediterranean region before Christian times.

Another result of the DNA-analyses is that C.sinensis (L) Osbeck is not in fact a basic biological species and it has been proposed a number of times that the sweet orange be labeled as a “convenience species” and for the moment I’ll stick to that, because south of the city of Chania, you’ll find endless orchards of oranges.

More about Citrus taxonomy at; http://www.corse.inra.fr/pub95/p95sr10.htm and http://www.answers.com/topic/citrus

Now, let’s forget all this theory about being species or not and have a look at the oranges as you will find them in the nomos of Chania.

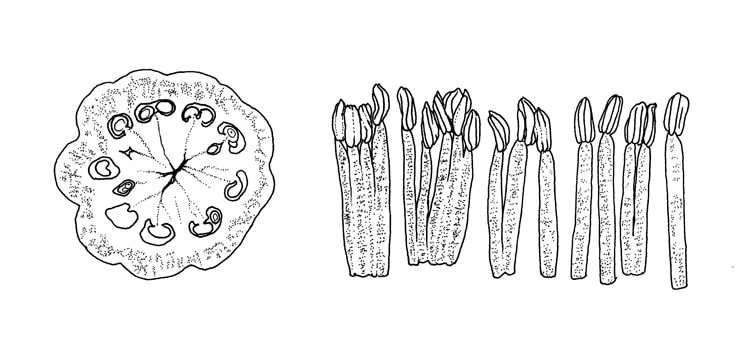

The orange tree is an evergreen small tree. The leaves are usually entire and the petioles often winged. The flowers are axillary: solitary or in short loose panicles, and the flowers are white (sometimes with a little purple on the outside), fragrant and strong-sweet-smelling. The flower has 4 or 5 petals and 15 or more anthers that are single or coherent in groups of three, four or more.

As Tutin in Flora Europaea says: it is a genus of considerable taxonomic difficulty. Some well known members in the Citrus family are: the citron (C.medica L.), the sour orange (C.aurantium L.), the pummelo (C.maxima Merril, formerly C.grandis Osbeck), the lemon (C.limon Burm.fil.), the tangerine (C.reticulata (Blanco), the lime (C.aurantifolia Christm.), and the grapefruit (C.maxima var. racemosa, formerly called C.paradisi Macf.), the sweet orange (C.sinensis), the mandarin (C.deliciosa).

However, some of the above mentioned species are of hybrid origin and there is much confusion about the genuine species within the genus Citrus. Some taxonomists recognize up to 170 species, others argue that all belong to only one large species because they are freely graft and cross-compatible for the most part.

In the Flora Europaea Tutin describes 8 european species:

1.C.medica L. (citron).

2.C.limon (L) Burm.fil. (lemon).

3.C.limetta Risso. (sweet lime). According to Tanaka (1954), a mutant of 2

4.C.deliciosa Ten. (Tangerine).

5.C.paradisi Macfadyen (grapefruit).

6.C.grandis (L) Osbeck (shaddock, pomelo).

7.C.auranthium L. (seville orange).

8.C.sinensis (L) Osbeck. (Orange).

Polunin mentions only three species, cultivated for their fruits and aromatic oils in Greece and the Balkans:

1.C.aurantium L. (seville orange)

2.C.sinensis (L) Osbeck (sweet orange)

3.C.limon (L) Burm.fil. (lemon)

Based on morphological and biochemical characteristics it has been proposed that the cultivated Citrus species comprises four original species of Citrus and that all the others are hybrids. These four basic species are: C.halimii Stone, C.medica L.(the citron) is perhaps the progenitor species for all acid citrus like lemons and limes, C.reticulata Blanco is perhaps the ancestor of all oranges and tangerines, and C.maxima (Burm.)Merril (syn. C.grandis) is the pummelo and shaddock and is probably the ancestor of the grapefruit.

However, recently (2007) using a novel DNA fingerprinting technique called AFLP, Xiao-Ming Pang et al suggest three ancestral species: C.medica (as ancestor of the sweet oranges and mandarins), C.grandis (as the ancestor of the grapefruits and pomelos) and C.reticulata (as ancestor of the lemons, limes and citrons).

All the other “species” are hybrids resulting from different combinations between these three ancestral species: ancestors crossed with ancestors, ancestors crossed with hybrids and hybrids crossed with hybrids, and crossings with Fortunella, Poncirus and other closely related genera. It has been suggested that both the sour orange and the sweet orange are hybrids between mandarin and pomelo; the clementine seems to be a hybrid between the mandarin and the sweet orange (which was already a hybrid between ......). Lemons are probably a cross between a citron and a sour orange (itself probably a hybrid of pummelo and mandarin).

The multitude of natural hybrids and cultivated varieties, including many spontaneous mutants, obscure the search for the center(s) of origin of citrus fruits. The origin of the citrus fruit trees is in the region of China and Southeast Asia and India. Far before the Common Era lemons, limes and oranges were cultivated in the Indus Valley and the citron was well known in the Mediterranean region before Christian times.

Another result of the DNA-analyses is that C.sinensis (L) Osbeck is not in fact a basic biological species and it has been proposed a number of times that the sweet orange be labeled as a “convenience species” and for the moment I’ll stick to that, because south of the city of Chania, you’ll find endless orchards of oranges.

More about Citrus taxonomy at; http://www.corse.inra.fr/pub95/p95sr10.htm and http://www.answers.com/topic/citrus

Now, let’s forget all this theory about being species or not and have a look at the oranges as you will find them in the nomos of Chania.

The orange tree is an evergreen small tree. The leaves are usually entire and the petioles often winged. The flowers are axillary: solitary or in short loose panicles, and the flowers are white (sometimes with a little purple on the outside), fragrant and strong-sweet-smelling. The flower has 4 or 5 petals and 15 or more anthers that are single or coherent in groups of three, four or more.

|

The calyx is present although generally not clearly divided into 4 or 5 sepals but mostly only irregular calyx-lobes.

The ovary has 8 to 15 locules and a long style with a capitate stigma. Under the ovary is, typical for Rutaceae, a large disk. The fruit is a globose berry (hesperidium) with several segments that are filled with a juicy pulp that is composed of stalked pulp-vesicles. Although there are 1 to 8 ovules in each locule, the modern oranges have no (or very few) seeds. |

Rutaceae normally have compound leaves. Don’t Citrus species have compound leaves? Actually, they do.

There are some more genera in the Rutaceae that are closely related to Citrus and were originally classified with citrus but later moved to their own genera. One genus is Fortunella, the kumquats. Kumquats are grown in Chania too, not on a large economic scale but you can find them.

Another important genus is Poncirus. One of its two species is Poncirus trifoliata L. Yes, trifoliata, commonly known as the trifoliate orange (the other species, which was discovered only in 1977, P.polyandra, Fumin trifoliata orange, does not occur in Greece). This species is commonly used as the rootstock for citrus, and because it is more hardy in wintercold than any other citrus, it is used in crossings with citrus in order to try to breed a frost-resistent orange. The leaf of P.trifoliata consists of three leaflets. In Citrus the two original leaflets at the sides are reduced to such an extend that in many cultivars they have nearly disappeared. Nearly. All that is left are two tiny margins at the sides of the petiole. In C.sinensis the petiole of the leaf are only narrowly marginated (see drawing). But in C.paradisi Macfadyen (the grapefruit) the petiole is very broadly winged, frequently up to 15 mm wide near the top, obcordate in outline. And in C.auranthium L. (seville orange) the petioles is broadly winged above, tapering to a wingless base. And there are two of the three leaflets: reduced to wings or even margins.

See large illustration, detail number 10

A beautiful picture of a flower of Ruta chalepensis showing its disk can be found at

http://www.west-crete.com/dailypics/crete-2010/1-19-10.php

There are some more genera in the Rutaceae that are closely related to Citrus and were originally classified with citrus but later moved to their own genera. One genus is Fortunella, the kumquats. Kumquats are grown in Chania too, not on a large economic scale but you can find them.

Another important genus is Poncirus. One of its two species is Poncirus trifoliata L. Yes, trifoliata, commonly known as the trifoliate orange (the other species, which was discovered only in 1977, P.polyandra, Fumin trifoliata orange, does not occur in Greece). This species is commonly used as the rootstock for citrus, and because it is more hardy in wintercold than any other citrus, it is used in crossings with citrus in order to try to breed a frost-resistent orange. The leaf of P.trifoliata consists of three leaflets. In Citrus the two original leaflets at the sides are reduced to such an extend that in many cultivars they have nearly disappeared. Nearly. All that is left are two tiny margins at the sides of the petiole. In C.sinensis the petiole of the leaf are only narrowly marginated (see drawing). But in C.paradisi Macfadyen (the grapefruit) the petiole is very broadly winged, frequently up to 15 mm wide near the top, obcordate in outline. And in C.auranthium L. (seville orange) the petioles is broadly winged above, tapering to a wingless base. And there are two of the three leaflets: reduced to wings or even margins.

See large illustration, detail number 10

A beautiful picture of a flower of Ruta chalepensis showing its disk can be found at

http://www.west-crete.com/dailypics/crete-2010/1-19-10.php