Vitis vinifera L.

Vitaceae / Vine Family.

The name sometimes appears as Vitidaceae, but Vitaceae is a conserved name and therefore has priority over both Vitidaceae and another name sometimes found in the older literature, Ampelidaceae.

When I speak about the grapevine, I have to make clear that I mean the cultivated grapevine, scientifically baptized Vitis vinifera subsp. vinifera (syn. subsp. sativa Hegi), and not the native wild grapevine, Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris (C.C.Gmelin) Hegi. One of the major differences between these two is that subsp. vinifera can be found abundantly everywhere in Crete, while subsp. sylvestris is a rare native of Chania. According to G. Sfikas, the wild, native form of the grape, subsp. sylvestris, can be found in Chania, in the eparchy of Kydonia. Another major difference is that subsp. sylvestris (the wild vine) is a dioecious climber (with both male and female plants), while subsp. vinifera has bisexual flowers (monoecious: every flower with ovary and anthers); under domestication, variants with perfect flowers appear to have been selected.

Subsp. sylvestris has small bluish-black acid-tasting fruits about 6 mm, with usually 3 seeds. Subsp. vinifera is cultivated since ancient times and ....

Subsp. sylvestris has small bluish-black acid-tasting fruits about 6 mm, with usually 3 seeds. Subsp. vinifera is cultivated since ancient times and ....

has larger fruits, 6-22 mm, which are sweet and vary in colour from green, yellow, red, or blackish-purple, with 2 or no seeds. It is often grafted on to stock from American species and cultivated in great quantities for its sweet fruits (grapes), wine-making, raisins or sultanas (small seedless grapes which are dried), etc.

Especially in the more isolated areas like the many abandoned small villages, the cultivated grapevine frequently escapes and becomes naturalized. These plants are monoecious like their cultivated parents.

The grapevine has been cultivated since ancient times; it was extensively grown in Crete according to the paintings on old vases, and from Greece they were first imported into Italy. The Romans introduced the grape into S.E. Europe. This is the "old world grape" or "European grape". accounting for more then 90% of world production, including cultivars such as: ‘Pinot Noir’, ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘White Riesling’, ‘Chardonnay’, and ‘Black Corinth’.

However, Vitis vinifera L. is not a very pure species. In the literature there are over 100 species in the Vitis-family (Vitaceae), about 60 of these are thought to be genuine species and more then 40 are questionable (probably hybrids between different species, many of them are very indistinct from each other). The origin of Vitis is almost entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and they are abundant in North America. Nearly every American state has its own native Vitis species.

When the grape root louse (phylloxera) reached Europe from north-central USA in 1860, the need for resistant rootstocks arose. Vitis labrusca L. (syn. V. labruscana Bailey) and other species native to the host range of the phylloxera (north-central USA) were hybridized with V. vinifera to produce a range of stocks with resistance. In addition to use as rootstocks, some hybrids were found which had both resistance and excellent wine quality attributes. V. labrusca itself was not very pure, probably contaminated with other native American grapes and vinifera grapes. Also, Vitis aestivalis Michauxwas used to obtain resistance to diseases in European hybrids, i.e., crosses were made between V. vinifera and V. aestivalis, as well as with other American species; these are primarily crosses between V. vinifera and one or more of V. labrusca, V. riparia, V.aestivalis, Vitis rotundifolia Mich.,Vitis rupestrisSch. or Vitis gegas.

The species occur in widely different geographical areas and show a great diversity of form. They are closely related and allow easy interbreeding and the resultanting hybrids are always fertile and vigorous. Thus the concept of a species is less well defined and more likely represents different ecotypes of Vitis that have evolved in distinct geographical circumstances.

Now, let's take a closer look the grapevine, and I mean the cultivated grapevine, Vitis vinifera subsp. vinifera.

Vine stems are "lianas" or woody, climbing vines and can be up to 35 m, climbing over trees, rocks or the pergola at the third floor of my neighbour's apartment. In cultivation it is usually reduced by annual pruning to 1-3 m. Most grapes have loose, flaky bark on older wood usually peeling from old stems in long shreds, but smooth bark on 1-year-old wood. The name vine is derived from the Latin 'viere' (to twist), and has reference to the twining habits of the plant.

The leafs are cordate, usually palmately 5- to 7-lobed, leaf margins irregularly toothed (dentate), alternate and stipulate. Well, stipulate? At the base of the petiole is a small scale with two tiny points and with a dot of frizzy white hairs, but you'll need a microscope to see the stipule. The same frizzy, long curly hairs can be found at the underside of the leaf; this arachnoid tomentum looks like the threads of a spiders cobweb. The veins at the underside of the leaf are also hairy. The upperside is glabrescent. Leaves can be quite large, sometimes more then 25 cm in width. In the eastern Mediterranean, Greece and Israel the leaves of the grape vine are itself used in the production of a common delicacy called domades : the leaves are wrapped around a vegetarian filling of rice, herbs and chickpeas or rice with lamb.

The plant climbs with the help of tendrils. The tendrils are branched and occur opposite the leaves at the nodes, normally opposite 2 leaves out of every 3, and automatically begin to coil when they contact another object. Also, after the formation of two or three complete flower-clusters, the following clusters are not completed but partially transformed in tendrils. Then, in summer, the flower clusters are completely aborted and replaced by tendrils.

The grape inflorescence is called a racemose panicle. These clusters of small greenish flowers are borne on new shoots at the nodes opposite the foliage leaves in the same position as the tendrils and are typically at the third to sixth nodes from the base of the shoot.

The numerous flowers are hermaphrodite, indiscrete small, green and actinomorphic.

The calyx consists of 5 very shortly lobed united sepals, is glabrous and undulate.

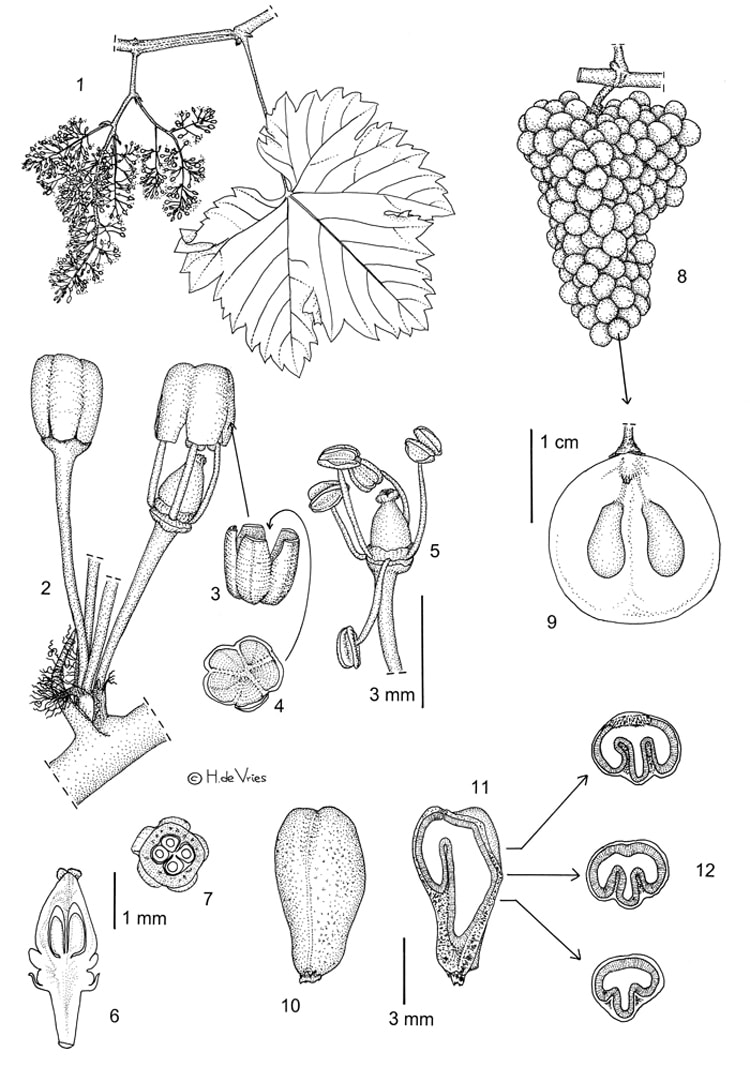

And, at last, we have come to that fascinating corolla. The 5 petals are small, about 5 mm and pale green, free from each other at the base, but are fused at the apex. This corolla is called a cap orcalyptra. It detaches from the base of the flower and pops off as one unit at anthesis without separating, see details 2, 3 and 4; detail 5 shows a blooming flower. In detail 3 you'll see an external view of the sepals or calyptra after it has been thrown off at anthesis; detail 4 is the same calyptra but an internal view.

Just as there are 5 sepals and 5 petals, there are 5 stamens. These are placed in a whorl that alternates with the sepals, so that they are placed in front of the petals, hence they are called antepetalous or alternisepalous or isomerous with the perianth.

The stamens are equal and free from one another and free from the perianth and are inserted at the base of the disk (yes, a disk and I'll get back to that later). The anthers dehisce via longitudinal slits and open introrse, that is in the direction of the centre of the flower. Most varieties are self-fruitful and do not require pollinizers ,in others pollination is accomplished by the wind and I doubt if insects play any role in this.

The gynoecium is superior, see detail 5. The ovary consists of two carpels forming two locules each with 2 ovules . Thus there is a possible maximum of four seeds per berry, see detail 7 for a transverse section of the ovary formed from two carpels with reflex edges. The placentation is axile with a ventral raphe, see 6 for a longitudinal section of the ovary. There is one style and one stigma.

As can be seen in details 2, 5 and 6 there is a disk between the peduncle and the ovary. In the two very different varieties (a black and a white grape vine) that I have investigated, the disk was more or less round and I could not find much of lobes or nectaries or glands. This disk is very distinct from the ovary and very probably has a function as a gland, because small flies love to visit the flowers, so these likely produce sugar or any sweet smelling excretion. Other cultivars are reported to have a five-lobed glandular disk at the base of the ovary.

The fruit is the well known sweet grape: green, yellow or dark purple, having a fine layer of wax on the surface, growing in pendent clusters or bunches. This is botanically a berry; it is fleshy with a juicy pulp, 6 - 22 mm, round to globose and does not open (indehiscent). Although most cultivars have no seeds by way of aborted embryos (polyploïdy perhaps playing a role as the basic chromosome-number is 2n=38, but several species have 57 (triploids) or 76 (tetraploids) chromosomes), the maximum number of seeds is 4. In some cultivars the development of embryo and endosperm is stopped, in other seedless cultivars fertilization does not occur, meaning that their berries are parthenocarpic. The seeds are pyriform, beaked, see detail 10. Detail 11 shows a longitudinal section of the seed revealing its layers as exoderm, mesoderm and endoderm, then the large white part is the large ruminate endosperm where in the lower part is place for a small upright straight embryo. Detail 12 shows sections of the seed at different heights, revealing the strange shape of the albumen.

Distribution: The native habitat of the grape vine is unknown, but it is probably native of Caspian and Caucasus region of S.W. Asia until S.E. Europe; it is now cultivated extensively in Central Europe extending northwards in S.W. Poland, W. Germany and The Netherlands, the whole Mediterranean region, Iran, China, Japan, N. & S. Africa, Australia, India, and Pakistan.

One of the most important products of the grape vine is wine. In Egyptian hieroglyphics the culture of grapes and wine making is described as early as 2440 BC. Probably the Phoenicians carried grape cultivars to Greece, as wine was known to both the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures and wine was frequently mentioned in the works of Homer and Aesop. To prevent the effects of heavy consumption of alcohol, wine was usually watered down at a ratio of four or five parts water to one of wine and served in "mixing bowls". Greek wine was widely known and exported throughout the Mediterranean basin, and amphorae with Greek styling and paintings have been found throughout the area. The Greeks brought it to Rome and southern France before 600 BC, and the Romans toke the grape with them throughout Europe. Grapes were then brought to the far east via traders from Persia and India. In our modern days alcohol is too often connected with violence and vandalism, so it is not strange that Dionysus the Greek god of both wine and revelry was.

Although glass bottles were known to the Greeks, they were more commonly used by the Romans. Cork closures, although known to exist at the time, were not very common. Therefore, the Romans used olive oil to "float" atop wine to preserve it from oxidation. Their oil method of preservation was apparently effective enough to keep the wine from evaporation up to modern day.

Grape facts on the Internet:

An good 3D model of the flower with its calyptra can be found at http://www.holtanatomical.com/action.lasso?-db=hP2.fp3&-lay=products&-format=results2.html&-recid=33564&-find

An interesting glossary on vines, grapes and wine can be found at

http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/hort_sci/fruit/winegrapesada/winegrapesada14.pdf

Many diseases threaten the culture of vines. The most well known is Phylloxera (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylloxera ). This is an American root aphid that devastated V. vinifera vineyards in Europe when accidentally introduced in the late 19th century. Attempts were made to cross in resistance from American species, but winemakers didn't like the 'foxy' flavours of the hybrid vines. Fortunately, V. vinifera grafts easily onto rootstocks of the American species, and most commercial production of grapes now relies on such grafts.

Especially in the more isolated areas like the many abandoned small villages, the cultivated grapevine frequently escapes and becomes naturalized. These plants are monoecious like their cultivated parents.

The grapevine has been cultivated since ancient times; it was extensively grown in Crete according to the paintings on old vases, and from Greece they were first imported into Italy. The Romans introduced the grape into S.E. Europe. This is the "old world grape" or "European grape". accounting for more then 90% of world production, including cultivars such as: ‘Pinot Noir’, ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘White Riesling’, ‘Chardonnay’, and ‘Black Corinth’.

However, Vitis vinifera L. is not a very pure species. In the literature there are over 100 species in the Vitis-family (Vitaceae), about 60 of these are thought to be genuine species and more then 40 are questionable (probably hybrids between different species, many of them are very indistinct from each other). The origin of Vitis is almost entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and they are abundant in North America. Nearly every American state has its own native Vitis species.

When the grape root louse (phylloxera) reached Europe from north-central USA in 1860, the need for resistant rootstocks arose. Vitis labrusca L. (syn. V. labruscana Bailey) and other species native to the host range of the phylloxera (north-central USA) were hybridized with V. vinifera to produce a range of stocks with resistance. In addition to use as rootstocks, some hybrids were found which had both resistance and excellent wine quality attributes. V. labrusca itself was not very pure, probably contaminated with other native American grapes and vinifera grapes. Also, Vitis aestivalis Michauxwas used to obtain resistance to diseases in European hybrids, i.e., crosses were made between V. vinifera and V. aestivalis, as well as with other American species; these are primarily crosses between V. vinifera and one or more of V. labrusca, V. riparia, V.aestivalis, Vitis rotundifolia Mich.,Vitis rupestrisSch. or Vitis gegas.

The species occur in widely different geographical areas and show a great diversity of form. They are closely related and allow easy interbreeding and the resultanting hybrids are always fertile and vigorous. Thus the concept of a species is less well defined and more likely represents different ecotypes of Vitis that have evolved in distinct geographical circumstances.

Now, let's take a closer look the grapevine, and I mean the cultivated grapevine, Vitis vinifera subsp. vinifera.

Vine stems are "lianas" or woody, climbing vines and can be up to 35 m, climbing over trees, rocks or the pergola at the third floor of my neighbour's apartment. In cultivation it is usually reduced by annual pruning to 1-3 m. Most grapes have loose, flaky bark on older wood usually peeling from old stems in long shreds, but smooth bark on 1-year-old wood. The name vine is derived from the Latin 'viere' (to twist), and has reference to the twining habits of the plant.

The leafs are cordate, usually palmately 5- to 7-lobed, leaf margins irregularly toothed (dentate), alternate and stipulate. Well, stipulate? At the base of the petiole is a small scale with two tiny points and with a dot of frizzy white hairs, but you'll need a microscope to see the stipule. The same frizzy, long curly hairs can be found at the underside of the leaf; this arachnoid tomentum looks like the threads of a spiders cobweb. The veins at the underside of the leaf are also hairy. The upperside is glabrescent. Leaves can be quite large, sometimes more then 25 cm in width. In the eastern Mediterranean, Greece and Israel the leaves of the grape vine are itself used in the production of a common delicacy called domades : the leaves are wrapped around a vegetarian filling of rice, herbs and chickpeas or rice with lamb.

The plant climbs with the help of tendrils. The tendrils are branched and occur opposite the leaves at the nodes, normally opposite 2 leaves out of every 3, and automatically begin to coil when they contact another object. Also, after the formation of two or three complete flower-clusters, the following clusters are not completed but partially transformed in tendrils. Then, in summer, the flower clusters are completely aborted and replaced by tendrils.

The grape inflorescence is called a racemose panicle. These clusters of small greenish flowers are borne on new shoots at the nodes opposite the foliage leaves in the same position as the tendrils and are typically at the third to sixth nodes from the base of the shoot.

The numerous flowers are hermaphrodite, indiscrete small, green and actinomorphic.

The calyx consists of 5 very shortly lobed united sepals, is glabrous and undulate.

And, at last, we have come to that fascinating corolla. The 5 petals are small, about 5 mm and pale green, free from each other at the base, but are fused at the apex. This corolla is called a cap orcalyptra. It detaches from the base of the flower and pops off as one unit at anthesis without separating, see details 2, 3 and 4; detail 5 shows a blooming flower. In detail 3 you'll see an external view of the sepals or calyptra after it has been thrown off at anthesis; detail 4 is the same calyptra but an internal view.

Just as there are 5 sepals and 5 petals, there are 5 stamens. These are placed in a whorl that alternates with the sepals, so that they are placed in front of the petals, hence they are called antepetalous or alternisepalous or isomerous with the perianth.

The stamens are equal and free from one another and free from the perianth and are inserted at the base of the disk (yes, a disk and I'll get back to that later). The anthers dehisce via longitudinal slits and open introrse, that is in the direction of the centre of the flower. Most varieties are self-fruitful and do not require pollinizers ,in others pollination is accomplished by the wind and I doubt if insects play any role in this.

The gynoecium is superior, see detail 5. The ovary consists of two carpels forming two locules each with 2 ovules . Thus there is a possible maximum of four seeds per berry, see detail 7 for a transverse section of the ovary formed from two carpels with reflex edges. The placentation is axile with a ventral raphe, see 6 for a longitudinal section of the ovary. There is one style and one stigma.

As can be seen in details 2, 5 and 6 there is a disk between the peduncle and the ovary. In the two very different varieties (a black and a white grape vine) that I have investigated, the disk was more or less round and I could not find much of lobes or nectaries or glands. This disk is very distinct from the ovary and very probably has a function as a gland, because small flies love to visit the flowers, so these likely produce sugar or any sweet smelling excretion. Other cultivars are reported to have a five-lobed glandular disk at the base of the ovary.

The fruit is the well known sweet grape: green, yellow or dark purple, having a fine layer of wax on the surface, growing in pendent clusters or bunches. This is botanically a berry; it is fleshy with a juicy pulp, 6 - 22 mm, round to globose and does not open (indehiscent). Although most cultivars have no seeds by way of aborted embryos (polyploïdy perhaps playing a role as the basic chromosome-number is 2n=38, but several species have 57 (triploids) or 76 (tetraploids) chromosomes), the maximum number of seeds is 4. In some cultivars the development of embryo and endosperm is stopped, in other seedless cultivars fertilization does not occur, meaning that their berries are parthenocarpic. The seeds are pyriform, beaked, see detail 10. Detail 11 shows a longitudinal section of the seed revealing its layers as exoderm, mesoderm and endoderm, then the large white part is the large ruminate endosperm where in the lower part is place for a small upright straight embryo. Detail 12 shows sections of the seed at different heights, revealing the strange shape of the albumen.

Distribution: The native habitat of the grape vine is unknown, but it is probably native of Caspian and Caucasus region of S.W. Asia until S.E. Europe; it is now cultivated extensively in Central Europe extending northwards in S.W. Poland, W. Germany and The Netherlands, the whole Mediterranean region, Iran, China, Japan, N. & S. Africa, Australia, India, and Pakistan.

One of the most important products of the grape vine is wine. In Egyptian hieroglyphics the culture of grapes and wine making is described as early as 2440 BC. Probably the Phoenicians carried grape cultivars to Greece, as wine was known to both the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures and wine was frequently mentioned in the works of Homer and Aesop. To prevent the effects of heavy consumption of alcohol, wine was usually watered down at a ratio of four or five parts water to one of wine and served in "mixing bowls". Greek wine was widely known and exported throughout the Mediterranean basin, and amphorae with Greek styling and paintings have been found throughout the area. The Greeks brought it to Rome and southern France before 600 BC, and the Romans toke the grape with them throughout Europe. Grapes were then brought to the far east via traders from Persia and India. In our modern days alcohol is too often connected with violence and vandalism, so it is not strange that Dionysus the Greek god of both wine and revelry was.

Although glass bottles were known to the Greeks, they were more commonly used by the Romans. Cork closures, although known to exist at the time, were not very common. Therefore, the Romans used olive oil to "float" atop wine to preserve it from oxidation. Their oil method of preservation was apparently effective enough to keep the wine from evaporation up to modern day.

Grape facts on the Internet:

An good 3D model of the flower with its calyptra can be found at http://www.holtanatomical.com/action.lasso?-db=hP2.fp3&-lay=products&-format=results2.html&-recid=33564&-find

An interesting glossary on vines, grapes and wine can be found at

http://www.cals.ncsu.edu/hort_sci/fruit/winegrapesada/winegrapesada14.pdf

Many diseases threaten the culture of vines. The most well known is Phylloxera (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylloxera ). This is an American root aphid that devastated V. vinifera vineyards in Europe when accidentally introduced in the late 19th century. Attempts were made to cross in resistance from American species, but winemakers didn't like the 'foxy' flavours of the hybrid vines. Fortunately, V. vinifera grafts easily onto rootstocks of the American species, and most commercial production of grapes now relies on such grafts.